The William James Association (WJA) is an organization that promotes work services in the arts, environment, and education. In addition, community … [Read more...]

Archives for November 2013

CDCR Certifies 48 Instructors

The Office of Correctional Education (OCE) recently held three one-week training and certification classes for 48 current instructors in the Inter-net … [Read more...]

John Kelly’s Inspirational Journey

John Kelly said he just sort of fell into a life of community service. His desire to help others led him down many different career paths. He was a … [Read more...]

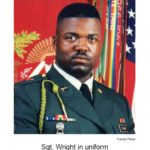

San Quentin Community Remembers Sergeant Dennis ‘Bubba’ Wright

DENNIS “BUBBA” WRIGHT August 24, 1974 - September 24, 2012 On September 24, 2013, the San Quentin community remembered Sgt. Dennis “Bubba” Wright, … [Read more...]

Folsom State Prison Celebrates The Graduation of 15 Women

Last July, 15 women doing time at Folsom prison graduated from educational programs ranging from high school diplomas to pouring concrete on … [Read more...]

LT. ANDERSEN RETIRES

Lt. Loren Andersen is retiring from San Quentin, the prison where he started his career, after 16 years of service with the California Department of … [Read more...]

American’s Prison Population Declines

With the closing of prisons in many states and initiatives to modify tough on crime laws, America’s prison populations are declining. Despite this, … [Read more...]

Lawmakers Scramble For Prison Funding

Throughout the nation, lawmakers are scrambling to find ways to fund the out of control costs of state correctional systems. The United States … [Read more...]

County Jail Construction Bogs Down

Six years after California lawmakers authorized $1.2 billion for counties to build more jail space, not a single county has finished construction, … [Read more...]

Brown’s Realignment Poses Challenges for County Jails

Governor Jerry Brown’s realignment strategy to reduce state prison overcrowding is presenting challenges for county sheriffs. California county jails … [Read more...]

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 5

- Next Page »