The first two weeks of parole can prove deadly.

A person released from prison is up to 129 times more likely to die from a drug overdose compared to the general public, according to a multi-state university study published in the academic journal Health and Justice.

Such numbers sparked a sharp reaction from San Quentin residents. Maxx Robinson and Clay Addleman believe the fatalities are proof that collectively, prison administrators and residents been having the wrong conversation.

“We need to start by getting people away from the uncontrollable action of their addiction,” Robinson said. “Whether its opiates or meth [methamphetamine], recovery begins with reducing harm and eliminating stigma.”

The study listed 83 different factors. Among those most closely linked to reducing the likelihood of overdose are access to treatment without consequences and recovery programs that are not solely focused on abstinence.

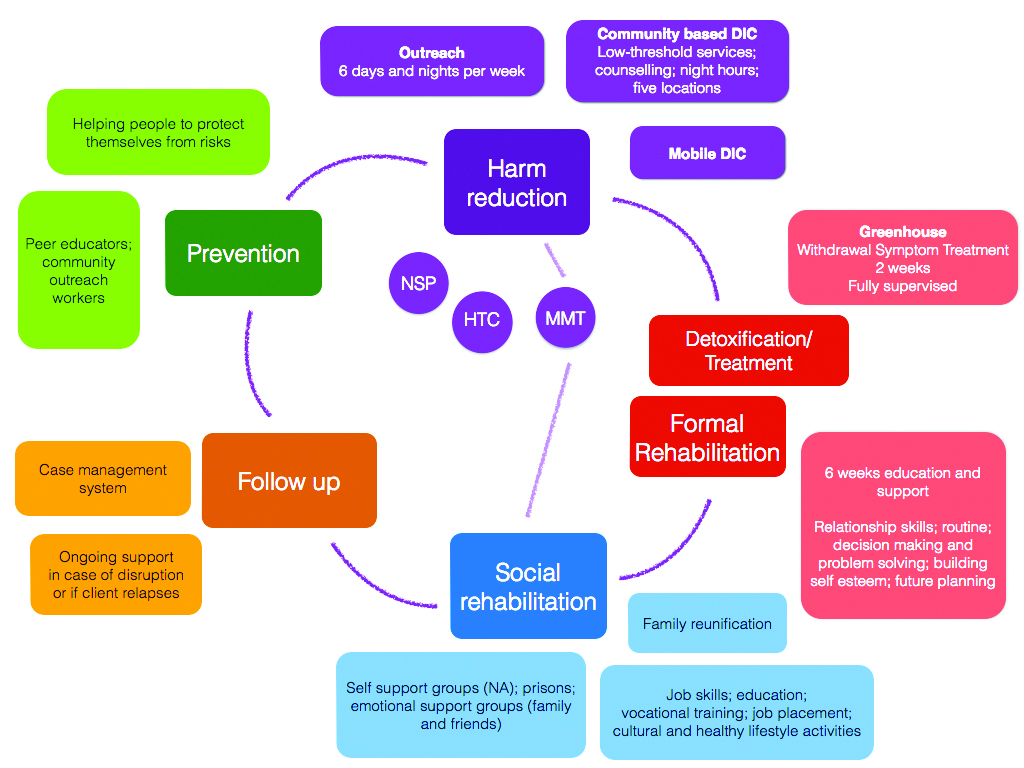

Both factors are now fundamental parts of California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s “harm reduction” model. One of its core programs, the Medically Assisted Treatment plan, offers Suboxone, a drug that suppresses the craving for hard drugs. Goals include not only preventing overdoses, but also improving personal well-being while freeing incarcerated people from the stigma of seeking substance use disorder treatment.

Addleman said the new model offers an important opportunity to engage and help those suffering from substance-use disorder, giving them confidence to embark on a process without stigma and negativity.

“Harm reduction gives people a chance to see the good in themselves, rather than how they might have failed,” Addleman says. “It’s telling them, ‘I love and support you, but I won’t assist you in shaming yourself for your addiction.’ Recovery is a many-pathways thing. It’s about finding the clarity to discover what works for you.”

For Addleman, that moment of clarity was what he now calls his “forever free” date.

Before then, he says, life was a giant chessboard focused around his addiction—how much he owed and to whom, who would still “front” him to buy drugs and who wouldn’t. Always looming was the life or death fear of what it felt like to experience withdrawal.

“On September 27, 2020,” Addleman said, “I began taking my suboxone through the medical assistant treatment program as prescribed, when prescribed. Now, my chemical imbalance is balanced. I don’t have to keep looking for this thing that is missing in my mind. I can go to class without being anxious about how I’m going to get through tonight. I got to a place of courage that allowed me to start programming.”

Addleman described finding a sense of purpose these past four years, one that includes serving others as a Peer Literacy Mentor. Most recently, both he and Robinson have begun work as Peer Support Specialists. Each said he has found joy in helping other residents recognize the value of the MAT program, not only as a means of taming their addiction, but also as an important step in parole suitability.

Both eagerly cite recent Board of Parole Hearing communications that strongly support incarcerated persons who elect to participate in the MAT program.

“The Board wants to see you taking your recovery seriously,” Addleman said. “They want to know that you are willing to ask for help when you need it.”

“But in prison,” Robinson added, “we’ve been telling people they are weak if they reach out for help, or use medically assisted treatment. There is so much institutionalized stigma behind getting assistance. It’s just another layer of toxic masculinity—the warped idea that you have to be strong enough to just quit your addiction by yourself.”

According to Robinson, the path to his own recovery started with the revelation that the MAT program embraced “treatment without consequences.” He was shocked to discover that CDCR medical staff was dedicated to helping him, not punishing him.

“In the beginning, when I first started on suboxone, I was playing with my doses and abusing it, taking more one day than the next,” Maxx said. “I was going through a lot when I first got to prison; I had recently broken up with a girlfriend, was settling into a very chaotic environment, and was basically willing to do anything to make my time a little bit easier.”

Robinson said he knew his levels were going up and down, and was surprised when the doctor monitoring his urinary analysis screenings didn’t alert custody staff.

“The doctor just pointed out to me that I was still abusing the suboxone like any other substance. He wasn’t interested in getting me in trouble, but in helping me correct my thinking.”

Robinson said that when he began taking his dosage properly, everything seemed to “level out,” that he no longer felt “all the ups and downs.”

“It was the first time I was able to function like I believe a normal person does,” he added. “I was able to have a level of motivation that I never had before, and to succeed in ways that I had never experienced before in my life.”

“Some of us,” Robinson said, “have been living in our addiction for a long time. Someone like that might never have experienced what it’s like to have a stable life. We spent years changing the chemistry of our brains. But when you use this like you’re supposed to, you might find that your life comes together in a beautiful way that you might never have expected.”

Both Robinson and Addleman said they are eager to help other residents with substance-use disorders understand the benefits of seeking help without consequences. They may be reached by submitting a GA-22, Inmate Request for Interview, addressed to the Peer Support Specialist Program.