No more shackles, cuffs, or escorts bring feelings of anxiety and gratitude

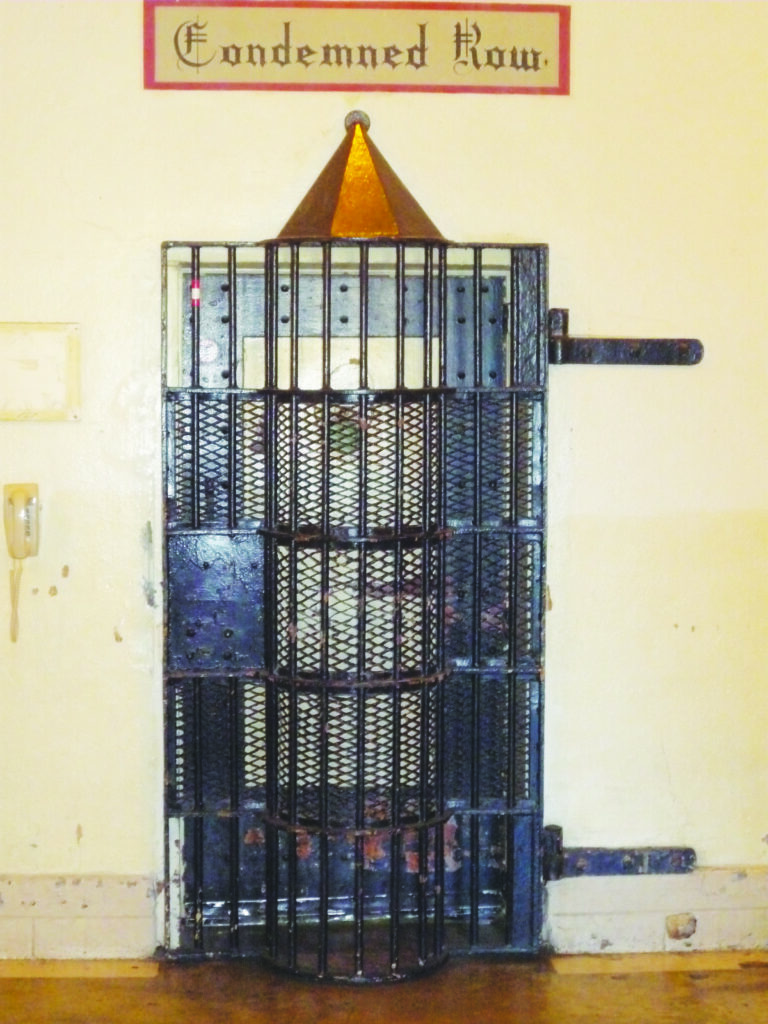

San Quentin’s infamous Death Row has been empty for more than a year. The institution’s East Block used to house more than 700 men who have been condemned to die by lethal gas or lethal injection. Where are they now?

About 80 prisoners from “The Row” — a name many of them call East Block — reside at California Health Care Facility in Stockton, California. At times, police, prosecutors, politicians, and prison officials refer to them as the “worst of the worst.”

However, rehabilitation does occur in unlikely places. Facing state-sanctioned execution for decades, figuratively and literally, some of The Row’s best experienced self-reflection and self-improvement. Police reports, court documents, and prisoners’ central files do not often reflect who they are after decades of incarceration.

“We’re just like everyone else in the [prison] population,” said John Davenport, 70. “We’re not quite as bad as people who didn’t get on The Row, but we got [some] bad ones.”

Davenport, incarcerated since 1980, arrived at CHCF on April 11, 2024, as one of the originals off The Row. “We thought we were going to be shackled when we got off the bus,” he said.

Like many CHCF prisoners from The Row, Davenport is part of the institution’s permanent work crew. “It’s like being on parole,” he said. “I like it.” He’s a kitchen worker and said he works hard. In exchange for his labor, he participates in a music program on weekends, where he plays the bass with other incarcerated musicians.

Jerry Grant Frye, 69, was incarcerated in 1985. While on The Row, he taught himself to play acoustic guitar. Like Davenport, he also spends much of his recreation time in the music program. “I haven’t played electric guitar,” he said. “I’m just learning.”

After nearly 40 years on The Row, Frye projects a pleasant demeanor. He appreciates CHCF and appears anything but dangerous. “It’s a whole different world,” he said. “It’s a complete shock.” He said that on May 18, 2022, his case received a “complete reversal,” but the attorney general has appealed, so now he is waiting for a ruling from the district court.

Since 1978, when California reinstated the death penalty (two years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the death penalty legal), more than 800 people in California received death sentences. The state executed 13 of them at San Quentin. The first was Robert Alton Harris, on April 21, 1992. Harris spent 13 years on The Row. The last was Clarence Ray Allen, on January 17, 2006, after 23 years on The Row.

Alex Demolle, 50, incarcerated for 26 years, served most of that time on The Row. His commitment offense is out of Alameda County. Like many of his contemporaries from East Block, he experienced a specific distress when he got off the bus at CHCF.

“I thought it was a setup,” said Demolle. He expected handcuffs and shackles, and a correctional officer escort to his housing unit, where he would serve most of his time in a cage. “Where’s the gun tower?” he asked himself.

Demolle lives in an honor unit and works as a “pusher,” a colloquial term at CHCF referring to Inmate Disability Assistant Program workers, as well as to some who work in the Peer Support Specialist Program. They serve to push other prisoners in wheelchairs at the sprawling medical facility. Prisoners in need of assistance do not have to ask for help. Pushers, or IDAP workers, will come to the aid of anyone they see who is mobility impaired.

“Just being able to move around freely without the gun being pointed at [me],” Demolle said, was both a shock and rewarding, especially, “without cuffs and being escorted everywhere.” He said that on The Row, someone brought everything to him. “Everything you need done [at CHCF] you have to do it yourself.” In addition to helping people, autonomy is what he likes about his move, and the fact that he doesn’t have to sit in his cell all day. “I have to remind myself to get my tray” (of food).

Jerry Rodriguez, 52, is a Peer Support worker who spent 25 years on The Row. He said only two things can happen in that place: “Go home, or die there. I’m still condemned.” Like others from The Row, he resides in the CHCF honor unit. He talked about how people with health issues experience a different type of incarceration. Helping them is his way to make amends for his past. “It’s something we’re actually doing in this health care facility.” He said that his actions, along with self-help groups, are helping him to heal.

Rodriguez attends a self-help group called Turning Point. Many of the other attendees are from other prisons, on “treat-and-return” status. They come to the meetings in wheelchairs, on four-wheel walkers, and with canes. “We become rewired in a way that is psychologically backwards,” Rodriguez said to the group about people who serve long terms in prison. “[This] group is not mandatory. People show up because they want to.”

California Governor Gavin Newsom placed a moratorium on executions in 2019. “[The state’s] death penalty system has been, by all measures, a failure,” he said. Newsom described how the death penalty “has discriminated against defendants who are mentally ill, Black and brown, or can’t afford expensive legal representation…,” the Death Penalty Information Center reported.

Demolle and Rodriguez are Black and brown, respectively. The former said he is trying for resentencing. Both work to help others as they work on themselves.

“Black defendants in California are up to 8.7 times more likely to be sentenced to death than defendants of other racial backgrounds,” David Greenwald of the Davis Vanguard wrote. “Latino defendants are up to 6.2 times more likely to face death sentences.” He offered other statistics to illustrate that any defendant is nearly nine times more probable to receive a death sentence when the victim of their crime is white.

According to the DPIC, in 2024, “California courts agreed that execution was not the appropriate punishment for at least 45 people on the state’s death row.”

As has been previously reported, Curtis Lee Ervin, 72, spent 38 years on The Row before his sentence was vacated. Evidence of racial bias was exposed in his trial. He was resentenced to manslaughter and paroled in August.

Donald F. Smith, 66, incarcerated since 1988, also spent decades on The Row before resentencing. He said, “The judge gave me LWOP” (life without the possibility of parole). He also lives in the honor unit.

Smith said another prisoner told him he did not want to take any self-help programs because he is a lifer, a long-standing, frequently cited reason. Smith said he explained, “This is an opportunity—The California Model.”

San Quentin resident Loi T. Vo arrived on The Row at age 18 and spent 29 years there before he was resentenced to life with the possibility of parole. He is scheduled to appear before the Board of Parole Hearings next January.

Vo recalled his early years in prison and talked about his time on The Row, where he met Ricci Phillips. Phillips spent 38 years there before his death sentence was overturned for a third time, reduced to LWOP. Today Phillips resides at CHCF in the honor unit.

“Ricci always had a story,” Vo said with a smile. “He would tell you stories that movies are made of. I miss our talks.” He said Phillips trained him to work as a clerk while on The Row, and hopes for the best for him.

Phillips had more than stories when interviewed. He had a precise way of wording an unspoken truth. “We woke up every morning [on The Row] knowing the state had an office building filled with people, authorized by the taxpayers, to carefully and meticulously plan our death.”