Anyone who has ever endured a goofy oaf, a bungler, a clod, a complete bonehead whose sudden and entirely unexpected appearance spoiled the moment — perhaps a cocktail party, a romantic date, a wedding, even a funeral — would know Kenneth Widmerpool.

The prototypical Widmerpool exists only on the pages of the Anthony Powell novel “A Dance to the Music of Time” (University of Chicago Press, 1976), but the world seems full of Widmerpools who probably have never heard of Powell’s hopelessly awkward character.

Widmerpool does not even count as the gigantic novel’s main character, but he clearly remains the most memorable one. Whenever the reader thinks that everything goes well for narrator Nicholas Jenkins, Widmerpool shows up and the plot tilts, shifts, skews, or ricochets in a totally unpredictable direction.

Did the author lose control of his characters? Did the author stand back and perhaps play an anthropologist who did witness a spectacle rather than write one? Powell did not go quite that far, for Jenkins’ self-effacement always returns the story to a rationality that allows the reader to continue in peace.

The novel has other unforgettable characters. Pamela Flitton seems one of the most dangerous women of all time, a person best avoided. Characters she meets can only hope that she forgets about them, but she never does: eventually, she victimizes them — not physically, not financially, but socially.

Despite the title, the 2,947 pages have nothing to do with dance or music. Much of the action in the novel revolves around cocktail parties, dinner parties, garden parties, and weekend parties in colossal country houses. The characters talk about literature and paintings. Very little else goes on.

In these interactions, Powell’s descriptions astound readers with profound insights into human behavior. Powell has vastly improved my ability to read body language and better to understand the unspoken meanings of social discourse. It turned me into a Jenkins aware of the real Pamela Flittons around me.

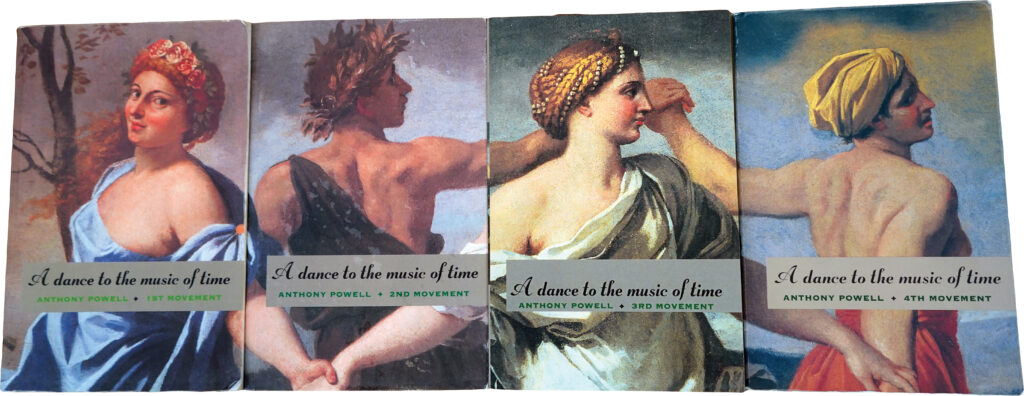

Set in Britain from the days following the Great War and reaching to the postmodern 1970s, the roman fleuve, or river novel, consists of four volumes (Powell called them “Movements” and “Seasons”) of 12 works published separately between 1951 and 1975. Its plasticity owes much to Marcel Proust’s epic “In Search of Lost Time.”

Written around the time of the accession of Elizabeth II, the novel allegorizes the conclusion of the slow-motion decline of the British Empire — every Golden Age must end. Jenkins’s friends Charles Stringham, a reckless aristocrat, and Peter Templer, a passionate womanizer, personify the decline.

Powell’s work has a writing style radically distinct from any other writer. Jenkins narrates the story in active-voice first-person point-of-view, but the author rarely uses the first-person singular pronoun, that ninth letter of the alphabet, which changes the characters’ agency. Jenkins often finds himself not acting but re-acting to whatever the world throws in his way, like Widmerpool.

This grammatical concept raises the question of whether any person, real or imagined, can ever really act independently, or actually runs on infinite sets of compounded re-actions. Bringing out such fundamental inquiries seems, to me, the purpose of literature; only great literature can accomplish such feats.

Powell, who pronounced his name pō’ɘl, died in 2000 at the age of 95. He had a close friendship with Evelyn Waugh, the author of “Brideshead Revisited,” my favorite novel of all time. Powell’s other novels, “The Fisher King” and “Afternoon Men” disappointed me. He also wrote plays and a multivolume memoir.

The novel’s ending prompted me to read it again, a second reading with much commentary penciled into the margins. The last sentence “Even the formal measure of the Seasons seemed suspended in the wintry silence,” always makes me wish for a fifth volume about a fifth Season.