The book “What’s Prison For?” by Bill Keller sheds light on crime and punishment, and the real purpose of incarceration.

Tough on crime should cater to the availability of rehabilitation, Keller says. The justice system’s distribution of long prison sentences allows the offender to return to society without any type of life skills.

Fair punishment and rehabilitation is the solution to lowering recidivism rates, Keller says. According to the book, the courts punish the convicted, but the prison should make sure the offender does not reoffend.

The objective of the crime bills mentioned in the book is to lock people up; these laws do not foster rehabilitation.

The book quotes Justice Potter Stewart as saying that retribution is a natural instinct and that it has been channeled into the criminal justice system in an effort to promote a stable society governed by law.

But criminologist Frances Cullen at the University of Cincinnati says punishment assumes that crime was an act of free will for which an offender should be held equally accountable to the harm caused by the crime.

Cullen’s statement conflicts with such laws as mandatory minimums, under which convicted offenders can receive longer prison sentences for non-violent crimes than those who committed violent crimes; a person should not receive a life sentence for a crime that does not cause physical harm and or death, Keller says.

The author reveals that in 1986 a federal law passed that mandated a minimum sentence for crack cocaine possession, a longer sentence than for powder cocaine. This defied the real purpose of What’s Prison For?

In 1994 California passed the Three Strikes Law; if you had prior felony convictions at the time of a subsequent arrest, it triggered an enhancement. One prior doubled the sentence; two priors triggered a term of 25 years to life.

In addition, an offender received five years for each prior serious or violent felony. The crimes prosecuted under this law caused an influx in the state’s prison population, which triggered mass incarceration.

The text defines rehabilitation: you learn to feel remorse; you learn about the cycles of violence, you learn about the factors that cause crime.

People who leave prison with job skills and insight on why they committed a crime are less likely to return to prison than those without it.

Jails and prisons that do not offer rehabilitation bear responsibility for the people on parole and probation who return to custody, Keller says.

The book asserts that some think it is cheaper to have a criminal in custody than for them to be out of custody. But an offender on parole who has a job and pays taxes contributes to public safety; a person’s helpful contribution to a society harmed by criminal actions can begin to heal both the person and society at large.

If we the incarcerated take advantage of rehabilitation, we can show that “tough on crime” legislation does not lower the recidivism rates, it only caters to mass incarceration.

Keller mentions Kayron Jackson, who served time for murder in New York State’s penal system; he spent years in prison establishing a reputation as a dangerous gang member.

Inflicted with some scars, and after months in solitary confinement, Kayron shifted his loyalty to a different crew, one whose gang colors were long sleeves and neatly creased pants. He became a rehabilitative programmer and got involved in self-improvement programs.

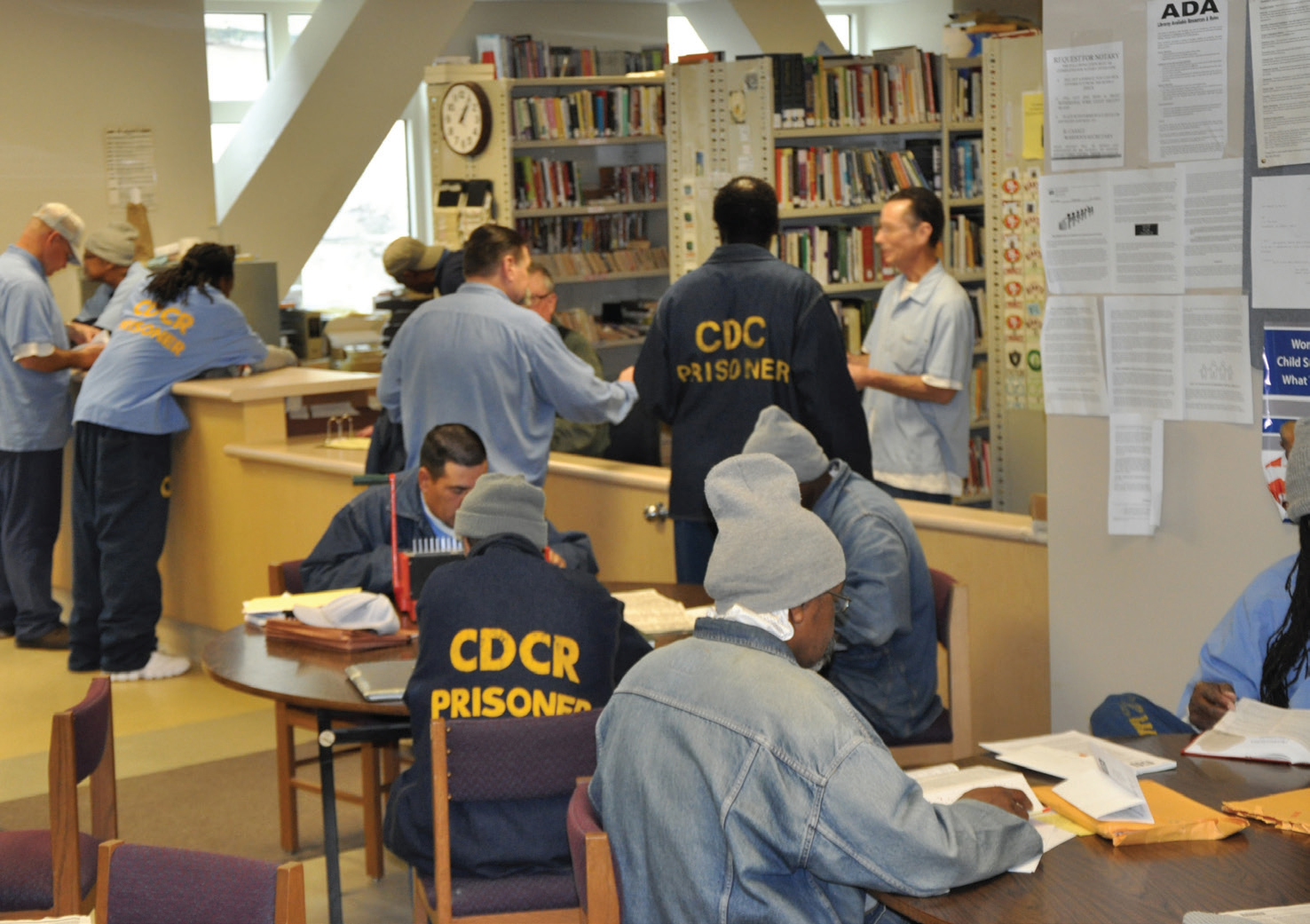

This example of self-help may or may not be familiar to us. How many incarcerated people across the country have an opportunity to reform? The residents at San Quentin State Prison have this opportunity.

Human kindness plays a big part in rehabilitation. How can a person reform when they are treated “less than?” Keller asks.

The book mentions Jody Lewen, director of Mount Tamalpais College, an onsite accredited college at SQSP.

The pandemic was a critical time at the prison. Jody and her staff of volunteers put together care packages of food, hygiene and stationery for everyone at the prison; they expressed this kindness twice. This kindness took place when the college staff could not enter the prison.

When the restrictions lifted, Mt. Tam continued to give the residents an opportunity at a quality education.

Since Keller’s book was written, the federal and some state penal systems have changed laws and policies curbing mandatory minimums; they are now moving toward the advancement of rehabilitation.

There is an abundance of insight within this book. I recommend all should read it. A healthy life comes from being properly informed.

We can think about those who never had a chance at self-improvement, how they fell into a lifestyle of ignorance. When the door opens, we leave with purpose. That’s what prisons are for, says Keller.